Culinary Cultural Appropriation, How Can You Identify It?

My Essay on Cultural Poachers

Cultural Appropriation in the Food Industry

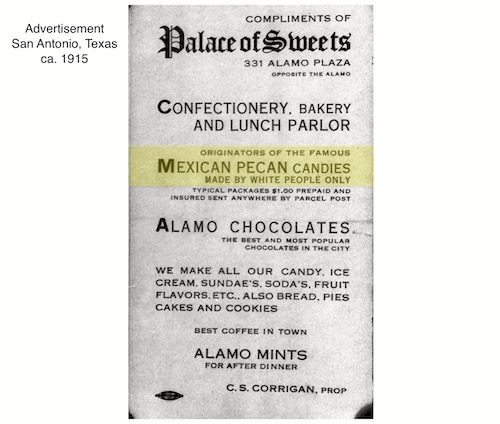

The comida casera, home-cooking of Texas Mexican American families, has been appropriated by commercial cultural poachers who in the process harm both the cuisine and the community that created it. I use the term, “cultural poachers,” to describe people who pretend to represent the best of a cuisine but cannot ever do so because their actions divorce the cuisine from its culture. Harmful is an apt description of culinary cultural appropriation, and sinister when it hides behind the pretense of culinary auteurism.

An auteur endeavor is the cook’s rightful artistic exploration and it should be championed. It’s far different from what is simply brash and harmful poaching. How to tell the difference? Three measures can be used to do so, and they involve taking a wholistic view of cooking, to understand that all cooking has the power to affect social relationships, with political and economic consequences. The three measures are voice, agency and money.

Does the entry into another culture’s cuisine diminish or silence the voice of the original creators of that tradition? Especially in the case of indigenous Texas Mexican food, the comida casera created and enjoyed by Mexican American families, the history is one of erasure and oppression. It’s been only the resistance and resilience of women cooks that have kept alive and brilliant the home cooking in Mexican American kitchens of South Texas and Northeastern Mexico. The cuisine is indigenous, Native American, and it developed over hundreds of years, resisting and prevailing over conquest and colonization.

Over time the indigenous people and their cuisine became “Mexican,” their roots erased from history texts, in popular discourse and by official state decree. In 1837 the Standing Committee on Indian Affairs of the Republic of Texas, in its report to President Sam Houston, declared that the Karankawa, Lipan and Tonkawa indigenous Texas people were to be considered “as part of the Mexican nation and no longer to be considered as a different People.” So the Texas Native Americans suddenly became Mexicans. It is cultural poaching when one enters another’s cultural sphere and the result is erasing their voice.

Destroying or silencing voices of the original creative cooks also harms the cuisine itself and our enjoyment of it. One example is how we understand and use chile peppers in cooking. Poachers of Mexican cuisine have defined chiles according to the amount of capsaicin in the seeds and membranes. There’s even a Scoville scale that assigns a number to each type of chile, so one can select properly the type of chile needed for cooking. But that ignores the real way that chiles work in the cuisine.

The original voices of Mexican cooking will explain that chiles are used for taste, color, aroma and texture. Heat “es lo de menos,” that’s a lesser consideration after complexity, depth of flavor and appearance. Whose voices are you silencing? That’s a good measure to determine poaching.

Agency is another consideration. As opposed to collaboration, poaching into another’s cuisine minimizes, even erases agency, the creative and intellectual ability of original artists. Indigenous Texas Mexican women created the dish we now call “chili.” They are the agents. But the credit is most often given to Texas cowboys with stories and legends that aggrandize them. Food poachers have erased the agency of indigenous women.

The third measure is money. Texas native peoples were dispossessed of their lands, and their economies of trade and travel were destroyed. Spaniards were the first to invade, then the French and later the Anglo immigrants landing on the eastern shores and migrating westward. Over the course of three hundred years the indigenous Mexican American community was deprived of capital and it is working capital that underpins the restaurant industry.

Cultural poachers who have access to capital grab the best of Texas Mexican dishes and turn them into a business that quickly overtakes the traditional small family-owned Mexican restaurants suffering the vestiges of historical capital deprivation. When taking another culture’s recipes and overtaking their market, food poachers cause economic harm. Not only that, but by doctoring traditional dishes with the more appealing and addictive ingredients of high fats, high salt and sugars, money-making becomes deadly.

Voice, agency and money are three measures that are always operating in the food industry, and the Mexican American community of Texas has been fighting with some success in a playing field that is historically stacked against them. Cultural poachers need to get beyond their “auteur” argument, that chefs have the right to artistic freedom and therefore can act desultorily, any way they wish. That is not an artistic vision.

There is an overriding value and vision that all artists must face: Can you have beauty without justice?

###

Send me comments about my essay, and here’s a bonus recipe for Chile Con Carne, “Chili.”

###

I think it all sounds very tasty. And please enjoy the food you like. the more you know about the history,the more enjoyable the food wll be. But please enjoy playing and discovering and exploring. Joy is what food is all about.

I like to put shredded cheese between two tortillas and fry it in a nonstick pan. Sometimes I put spinach, onion, or broccoli in it. It is a quick, healthy meal.

But is that the oppression and cultural appropriation that you talk about?

I like to put shredded cheese between two tortillas and fry it in a nonstick pan. Sometimes I put spinach, onion, or broccoli in it. It is a quick, healthy meal.

But is that the oppression and cultural appropriation that you talk about?

Adan – thank you for this clear outline of culinary appropriation. You rightly say at the beginning ‘An auteur endeavor is the cook’s rightful artistic exploration and it should be championed.’ Without the license for such auteur endeavour, we Anglo Australians would be dismally limited.

When I read recently that British chef Jamie Oliver had hired an appropriation consultant, I snorted. From the very beginning of his career, Jamie has cooked mainly Italian food. But his use of Italian recipes and ingredients does not harm Italiancooks or culture. Italy is big enough and established enough to look after itself.

But in the case of Texas Mexican American cooking, this clearly happened when the gringos trampled all over and obliterated your roots.

In my book abou (non-Indigenous) t Australian Cooking,The Getting of Garlic, I quote Imaginary Homelands, in which

Salman Rushdie writes of his book Satanic Verses that it:

‘celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the

transformation that comes of new and unexpected

combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas,

politics, movies, songs. It rejoices in mongrelization

and fears the absolutism of the Pure. It is a love-song

to our mongrel selves … Perhaps we are all, black,

brown and white, leaking into one another … like

flavours when you cook.

This is a powerful definition of what the best Australian chefs are doing, ‘using diverse paradoxical and

sometimes contrary influences to make something that will be entirely their own’. Australian food is, as

Rushdie writes of his book, ‘a love-song to our mongrel selves’, flavours, ingredients and origins leaking into

one another

It is this loosely linked network of Australia’s multicultural population, each with its own ideas of what

and how to eat, that at the same time denied us thechance of a traditional food culture and gave impetus

to our most talented chefs at our high public tables to daily create a mongrel cuisine, a cuisine lauded globally.

More bricolage than appropriation

Hi, Susan, thanks for your kind words, and about the chiles: I think it’s a good idea to simply look at Mexican recipes to see how in making moles, adobos and other dishes, the seeds are removed. Of course, sometimes you want the seeds to raise the heat. It all depends on each dish. That is a good way to see how to manage the level of capsaícin in each dish.

Hi Adán, I love your cookbooks (both) and emails. A question of help/resources – I had absolutely no idea that chilis and ‘hot’ were not really connected, as far as what goes best in the dish. Do you have a resource recommendation to help me understand how certain chilis complement a dish and what’s best in what? I hope this makes sense. As a native Virginian who has lived in Texas for many years, I love Tex-mex and am also growing to appreciate the simpler food in your books as well as ‘real’ Mexican recipes. Many thanks for the tasty education!

sue