6 Takes On Tacos In Texas

Writers who examine, probe and dig into tacos always have a point of view, a starting point that comes from their personal history, and their ancestry. When they write or scribble their taco stories, they straddle and stride from somewhere between a totem and a stereotype.

In Mexican gastronomy, the taco is somewhat similar to a totem, an object that serves as the emblem or the evocative symbol for a people and its ancestry. A totem invites exploration of meaning, traditions, and family histories.

By contrast, that same taco can also be a simplistic and harmful stereotype that sparks attention because it is instantly recognizable and can be easily linked to a people. Different from a totem, the stereotype does not invite exploration but is constructed as a mental picture of an oversimplified opinion, prejudiced attitude, or uncritical judgment.

Looking across Texas, these six profiles of taco writing steer toward the totem kind of writing and show a wide range of approaches. One follows a calling that links to personal discovery of self and family, another wants to be a conduit, while still others want to give voice to their land, their traditions and their ancestors.

Sergio Palacios

Sergio Palacios

Sergio Palacios, moniker, @thetacotourist on Instagram, combines writing with video-making to frolic and high-five his favorite taco locales. He started creating videos 18 months ago when he was going through a break-up. Finding he had time on his hands, what could he do?

Born in Madisonville, just north of Texas A&M, College Station, Sergio went to college in San Marcos and calls Pflugerville, Kyle, Buda, Austin (the general area from San Marcos to Georgetown) “my territory.” But his Instagram posts have touted tortillas in places like Denver, San Diego and in Utah. But no matter the place, he makes this constant caveat about the comida casera, (home cooking) of his childhood: “My mom makes the best tortillas de harina in the world!”

A business analyst with a financial company in Austin, Sergio travels as much as he can to engage taco makers and vendors, seeking to find what’s behind the surface of their tortillas and “letting their passion ignite mine.” It’s the digital chasm that immediately affronted him, the isolation that internet and tech policies have created by crafting regulations that relegate poor Mexican Americans to the shadows and margins of the digital world. Poor people don’t have equal access to digital technologies and so their business growth is stunted. It hurts the taco maker, the wider economy, and it hurts the taco lover.

“The real gems don’t have a Google appearance, so if you’re looking just at big media, you are losing out on good food,” says Sergio. It’s great to get those top 10 lists from Yelp or Eater, or those others, he says, but at the same time, “I don’t know how deep they’re getting into, their list…they are looking for what is much more obvious and popular.”

Sergio says he’s looking for “the person who’s been working in the shadows for ten years.” He finds them through online discussions, and his trips end up as video romps, even adventures, although eating a whole Habanero chile as he recently recorded in one of his video posts— was definitely a bad idea.

Sergio says he is now putting more time into the intricacies of writing, recording, editing, because he feels a responsibility toward his community, to “grow the culture in a positive manner.” So, writing about tacos is really writing about his community, his culture, his mom, his ancestry.

Armando “Mando” Rayo

Armando “Mando” Rayo

Armando, “Mando,” Rayo wants to voice his culinary heritage, and tacos are the vehicle. He lives in Austin, has co-written two books about tacos and now produces and co-hosts a video series, “United Tacos of America,” on El Rey Network.

The beginning of Mando’s journey into writing about tacos is a natural and simple one as he explains it: “It’s part of my culture.” When you’re eating a taco, you’re involved in culture because “food is our culture,” he says. But to understand that culture you have to go beyond the taco as an object. He says that in the past, writers dealt only with the object and did not pay attention to the context in which it was made, how it was made and who made it.

He describes himself as a taco journalist. “Maybe we’re in the Rio Grande Valley and we’re talking about barbacoa, or we’re talking about the Matamoros street-style tacos. But we have to talk about the issues that are happening in the community. And a lot of it has to do with immigration. A lot of it has to do with gentrification. A lot of it has to do with erasure of culture. And so that’s what I try to bring in with taco journalism, is going deeper and deeper and deeper and pulling away the layers of what’s behind that taco.” He continues, “for me, taco journalism is a way to go deep into some of these stories, deep into some of the people, the communities, and then the connection to the issues that are important to many Mexican communities, Mexican or Mexican Americans, Chicanos, Latinos.”

He was born and grew up in El Paso, in the Ysleta neighborhood, and even lived in El Segundo Barrio right next to the bridge that goes across the river to Ciudad Juarez. “It’s right downtown, next to the bridge, basically. It’s kind of where everything happens, where everybody crosses over.” Those flavors and surrounds enlighten how he looks at tacos. It’s the prism for the character of a people. And gender is key. When it comes to food and tacos, women have been relegated to the shadows.

“Who gets the credit?” Mando asks. It’s the homage to the taquero that’s always there, “but behind a good taquero there’s a good tortillera, there’s a good cocinera there’s an abuela, it’s a mom, it’s a sister.”

“So what we try to do is really think about a lot of those related issues that come into play within the culture and the food.” In the final analysis, taco journalism is about social justice and the work involves promoting understanding about what is community.

Mando promotes understanding with tacos. “You break bread. For us, we tear a tortilla together. And it starts there. It starts with a conversation. But it starts also with putting that taco inside your priority to really experience or getting a taste. Literally getting a taste of the culture. And then it kind of goes from there.”

José Ralat

José Ralat

José Ralat was born in Puerto Rico and grew up in New York City. He now lives in Dallas and says that he began writing about tacos because he needed money to support his family, and it was a subject that interested him. José explains that his wife “who is Tejana, introduced me to the wonderful variations and diversity of tacos. She has this deep cultural knowledge and she is willing to share it with me.”

As he learned more about tacos, he became more passionate about them, looking into the stories about the people who are connected to the tacos. His current job is at the magazine, Texas Monthly, where his title is taco editor. He says that he likes to write food criticism but he also likes to write about culture and to tell human stories. Religion and cultural identity are tied to the taco as a cultural product, he says.

He believes that the deep knowledge about tacos is constantly at risk of being lost and refers to the history of Puerto Rico to make the point. “The first thing the US colonizers did was erase our agriculture.” He explains that local agriculture was supplanted by underwear factories and drug manufacturers. By destroying the local sourcing of food, colonizers insured that survival was at their whim. From this vantage point he says that he understands the importance of food in relation to cultural identity and self-worth.

He mentions that his son is part Mexican American and deserves to have access to the magazine food stories that he writes. “It deserves a voice,” he says, “I just want to be a conduit for that.”

Andrés Macario Garza Vela

Andrés Macario Garza Vela

Andrés Macario Garza Vela was born in Monterrey and at nine years of age moved to the Rio Grande Valley and says, “my main inspiration for research comes from my growing up in the Valley.” Andres writes about food, tacos and especially about corn tortillas and ancestral roots on Instagram and on the website, andresmgarza.com.

Moving to Austin for college, they studied anthropology and graduated just as the Covid -19 pandemic hit hard. (Andrés prefers to be identified with a gender-neutral pronoun.) They made the decision to move back to the Valley and reestablish their native culinary roots. “I had this really big complex of not appreciating my own Mexicanness or my own culture.”

A transition to self-awareness followed while in college, and it was linked to food. “I remember leaning towards other foods, foods that I thought were of a higher class, which was things like sushi, Japanese cuisine, and imperialist cuisine. I never had a moment to look back at my own roots. And the past three, four, five years, has just been me trying to make up for that lost time, trying to make up for what I didn’t appreciate in the time growing up.”

“I’m only 23 now. I did lose 10 years of not appreciating what was right in front of me.”

Now Andrés approaches tacos with the fervor of their grandmother and the knowledge acquired while working and making tacos at the nationally acclaimed “Nixta Taquería” restaurant in Austin that was recently featured in the New York Times. Using the corn flour brand, Maseca, is totally a non-starter, so Andrés now operates a molino and sells tortillas made with freshly ground masa. “A barbacoa taco feels like a true celebration, and having fresh tortillas is something that is entirely beautiful.”

Writing about tortillas, tacos and culture on social media is based on field notes of the “comida casera” that is thriving in the Rio Grande Valley. It’s the cooking that often takes place on the margins, in the shadows of the licensed and controlled food industry. They report that vendors still sell the delicious barbacoa tacos that are cooked in the traditional way, cooked in pozos (hole-in-the-ground), “but it’s not accepted by the local governments at all, except for only one place, which is Vera’s,” the famous taquería in Brownsville.

Andrés says that licensing issues become the stories, including “people finding those loopholes.” Until now it has been difficult to document and release that information without getting people in trouble. Nonetheless, the central writing is about tacos de barbacoa and carne asada and indigenous roots. “I want to continue researching the border, the border foods, the border history and the greater border region.”

Vianney Rodriguez

Vianney Rodriguez

Vianney Rodriguez is a native of Aransas Pass, 20 minutes from Corpus Christi. She has written a cookbook, “The Tex-Mex Slow Cooker,” and also “Latin Twist” a book with recipes for Latin-inspired cocktails. Vianney narrates her culture through her dishes, beverages and, of course, tacos which she links to her native Texas landscape.

“De aquí soy (I’m from here), you know. I don’t plan to move. I don’t think I could live anywhere else. So I’m always sharing about Texas. I write about all the things and flavors and smells that I grew up eating.”

When she was growing up in Aransas Pass, she says, a natural part of growing up was crossing over to the other side to visit family. Like so many native Mexican Americans whose ancestors have inhabited the coast for thousands of years, she has family on both sides of the river. Both sides comprise one landscape, and that’s her home. She says that Texas is a landscape from where food emerges and is linked to family. It’s a heritage passed on through generations and it will never be lost. Tacos are part of that.

“To me, [the taco] that’s a power food. I remember my mom in the morning, packing tacos for my dad for lunch. In the morning, before you go to school, you have a quick taco. It’s such a big part of our culture.”

Vianney doesn’t look for taquerías to review and recommend. That’s because she is first and foremost a cocinera, a cook and culinary artist. She writes about the tacos that she creates in her kitchen and posts recipes on Sweet Life. “I just share the tacos that I grew up with. Like, I do carñe asada con cheese and I do bean and cheese, and sometimes on stories I’ll share, ‘this is what I’m having for lunch.’ And it’s a corn tortilla straight off the comal with a slice of aguacate and some sal. And I’m like, ‘Has there ever been a greater combination than this?’ ”

She says, “the food and comida, and my people and my gente and my culture and my cultura have shaped me into what I am today. So I feel like I’m just so honored and I love it so much that I want to share it.”

Cooking eventually led to writing because the traditions and recipes are strong and compelling. There was a lot of interest in her writing and sharing about her cooking from magazines like Southern Living. “The writing at first was a little hard, and then I thought, you know what? I’m just going to share what the food means to me, the story behind it, qué es, because a lot of people wanted to know how to make the food. So I started just giving tips and little stories and how my abuelita did it and my mom did it. And then the more I did it, the more at ease I became with it. And then after a while, it was just all about the food and the story. So that’s how it kind of started for me.”

Vianney finds that “families have been making tacos for generations, and they’ve got it really down.” The back stories of those families are key because, like her own family, they are the source of the traditions. “People are interested and people want to know about it. So yeah, I’m always and forever sharing tacos.”

Edmund Tijerina

Edmund Tijerina

Edmund Tijerina was Born in El Paso, and was raised in both Houston and San Antonio, since he had family in both places, and they traveled back and forth. He has been a journalist since the 90s when he lived in Milwaukee and was also the chef/owner of “La Estrella” restaurant. Having been a chef/owner gives Edmund a special insight when he writes about tacos, food and restaurants. He was the restaurant critic for the San Antonio Express-News and later the food and beverage editor.

He says that he enjoyed two aspects of his writing job at the newspaper. One was talking to home cooks about their family recipes and about their personal stories, “how their cultures and their family histories found their way or were expressed in their food.” The second was writing profiles of restaurants and being part of the growth of the San Antonio food scene that now has garnered national attention.

Today Edmund works in strategic marketing and communications and also writes for San Antonio Magazine where his title is contributing writer. He continues to delve into the cultural meanings that surround tacos. He explains that Mexican tacos are one thing, but Mexican American tacos “come very much from the Mexican- American experience. They’re different ingredients, different palates, different ways, different concepts of making tacos.”

“Now, what I will tell you is that there are some people who try to do little mashups of tacos, but I actually avoid writing about them. This is where you start to talk about cultural appropriation.” Edmund prefers to explore the delicious evolution of the South Texas and Northeastern Mexico traditions. He focuses on San Antonio to explain.

“Oh, I think Mexican-American tacos will always have a future. They’re a part of our heritage. I would compare the Mexican-American tacos to the way that pizza napoletana is native to Naples. In Naples, you’re not looking for your creative takes on pizza. You’re looking for the home of that pizza, looking to calibrate your palate to know that this is what a Naples style pizza should be. I think we have that same thing in San Antonio.”

Edmund sees San Antonio as part of the larger region that is home to the Mexican American taco. ”Here is where you find out what should a bean and cheese taco taste like. What should a puffy taco taste like.” During his career he has covered and written about LA tacos, mid-western tacos and the rest, finding them all delicious. But as for San Antonio, “We’re the heart of Mexican-American tacos and that will never die. There will always be room for the down-home South Texas/Northern Mexico tacos [that have a home] in San Antonio.”

Conclusion

The taco is not just an artifact but a culinary art form that can be compared to the original use of Native American totems where the entity, or totem, serves as an emblem or symbol representative of the community. Writing about tacos in this way necessitates writing about personal and family histories, for the totem represents ancestry. Writing in this way addresses social injustice, gender inequities, and culinary roots. It’s really all about the intricate and interesting lives of people who make and share this important traditional food.

Taken as a snapshot of the rich expressions that food writing represents in Texas, these six takes on tacos offer views that are colored by specific personal places. Whether it is being a conduit, or sharing artistic expression, or savoring and championing family traditions, there will always be new horizons for tacos.

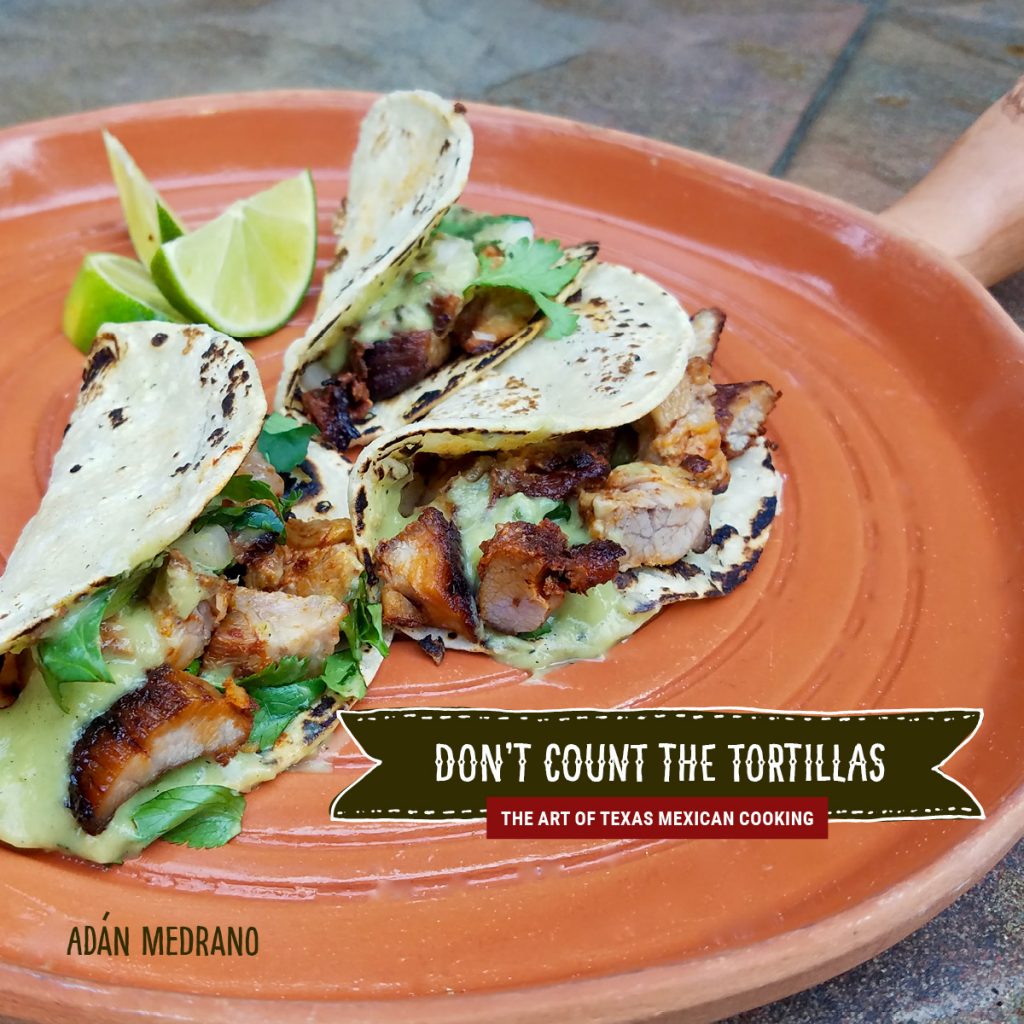

Don’t Count The Tortillas: The Art of Texas Mexican Cooking

Don’t Count The Tortillas: The Art of Texas Mexican Cooking

The best taco I ever ate was in a home in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. The floors were dirt, the bathroom was outside and the stove was wood burning but everything was neat and very clean. The tacos were made with ground beef with tiny pieces of potato mixed in to make it go farther, fried in lard, and delicious! Here in Tucson, Arizona, we have some pretty authentic Mexican food, but nothing like the one I described.